by Scott Speidel, Florida State University

Fear of “Anti-Semitism” Provides an Opening

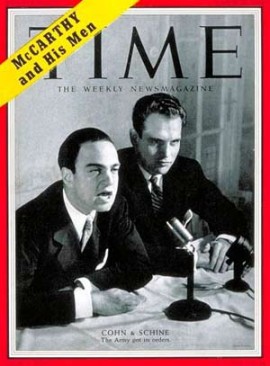

MCCARTHY’S REPUTATION was destroyed chiefly by the feud that two staffers on his Subcommittee on Investigations, Roy Cohn and G. David Schine, conducted against the United States Army, contrary to McCarthy’s wishes.

Under pressure from influential Jewish columnist George Sokolsky and the Jewish president of the Hearst Corporation, Richard Berlin, both purported anti-Communists, McCarthy announced on January 2, 1953, that 26-year-old Roy Cohn would be the chief counsel of the Investigations Subcommittee. Cohn, the son of New York Supreme Court Judge Albert Cohn, had been well served by his Jewish connections in the past, having been hired as an assistant U.S. attorney immediately after passing the New York bar examination. Cohn himself later admitted that he was hired by McCarthy primarily because he was a Jew:

“There was a growing slander abroad in the land . . . that McCarthy was a Jew-hater . . . and he wanted to deflect it. I was the obvious answer, and the alternative — [Robert Kennedy,] the son of the well-known, well-documented anti-Semite Joseph P. Kennedy, the former pro-Hitler ambassador to the Court of St. James — was the last person McCarthy needed to head his committee.”

It probably need not be stressed that the Jews themselves were the source of this “slander” that McCarthy felt obliged to counter.

Thus, McCarthy was stuck with Cohn; privately he expressed the fear that if Cohn resigned for any reason the charge of “anti-Semitism” immediately would be raised against him again.

Furthermore, with most of the news media already solidly against him, McCarthy was desperate for some favorable press coverage. Illinois Republican Senator Everett Dirksen commented, “Cohn was put on the Committee by the Hearst press, and Joe doesn’t dare lose that support.”

Cohn, who died of AIDS in 1986, was a homosexual, and rumor of the perversion became widespread after Cohn had brought another young Jew, G. David Schine, onto McCarthy’s staff. According to Cohn himself in his autobiography, Cohn and Schine were then rumored to be “Jack and Jill.” This rumor was undoubtedly a great embarrassment to McCarthy, since the controlled media had not yet succeeded in making homosexuality fashionable, and homosexuals were among the security risks to be investigated.

At Cohn’s insistence, Schine was accepted as an unpaid “chief consultant” on Communism. Schine’s credentials for this position were that he had authored a pamphlet, Definition of Communism, which his wealthy parents had allowed him to distribute in their hotel chain. This pamphlet gave incorrect dates for the Russian Revolution and the founding of the Communist Party, confused Marx with Lenin, Stalin with Trotsky, and Kerensky with Prince Lvov, and got Lenin’s name wrong. The Jewish millionaire-playboy was thus highly qualified, in Cohn’s view, to be a consultant.

McCarthy hoped that he could save himself from accusations of “anti-Semitism” with Roy Cohn, and if necessary, with Dave Schine. But the day McCarthy accepted these two Jews as his assistants was the day his downfall really began.

As the son of a Jewish multi-millionaire, Schine had avoided the draft for the Korean War by getting himself classified 4-F. As soon as he became a staff member of McCarthy’s committee, however, at the instigation of left-wing journalist Drew Pearson the Army reclassified Schine 1-A and drafted him. Thus, the stage was set for Roy Cohn to involve McCarthy in a dispute with the United States Army.

Army-McCarthy Hearings: Dragged Against His Will

It is clear that McCarthy was dragged into this dispute against his will. Army lawyer John Adams relates:

“Senator McCarthy spoke out quite freely about his irritation over Schine. He told me that the individual is of absolutely no help to the committee, was interested in nothing but the photographers and getting his picture in the papers, and that things had reached the point where he was a complete pest. McCarthy stated to me quite emphatically that he was anxious to see this individual drafted, and . . . he hoped . . . we would send him as far away as possible ‘to get him out of [his] hair.” . . . “Send him wherever you can, as far away as possible. Korea is too close.'”

Cohn raised hell with the Army, first threatening revenge for the drafting of Schine, then agitating for special treatment for his putative boyfriend. John Adams stated in a January 21, 1954, meeting in Attorney General Herbert Brownell’s office that demands for the names of Army loyalty-board members usually were preceded by flare-ups over the reassignment of Schine. McCarthy was not happy about this behavior, and he privately complained that Cohn was indeed carrying out a vendetta against the Army on account of Schine.

McCarthy had instructed Adams on December 17, 1953, that, having learned the extent of the interference Cohn and Schine were causing for the commanding general of Fort Dix, he wished the Army to discontinue all special treatment for Schine. Subsequently, the alleged anti-Communist Jew, columnist George Sokolsky, contacted Adams repeatedly, continuing to urge special treatment for Schine. On February 12, 1954, Sokolsky went so far as to tell Adams that he, Sokolsky, would “get them to drop all this stuff they are planning for the Army [i.e., McCarthy’s investigation of Communist subversion in the Army],” if a special assignment were arranged for Schine. It seemed that Sokolsky was more concerned about the comfort and convenience of one fellow Jew than about the national security of the United States — or he was deliberately exacerbating the animosity between the Army and McCarthy.

Meanwhile, in late January 1954 a story in the New York Post featured Fort Dix recruits complaining that Schine lived among them like a visiting dignitary — and Joseph McCarthy was taking the blame.

Secretary of the Army Robert Stevens said that he was wary about “discriminating against” Schine, because Schine was a Jew. Likewise, McCarthy said that he was afraid to fire Cohn, “because [I] might be accused of being anti-Semitic.” Here we have the Secretary of the Army and the chairman of a Senate committee, both paralyzed by fear of being called “anti-Semitic,” allowing 26-year-old Roy Cohn and the utterly inconsequential G. David Schine to walk all over them.

It was not only the fact that McCarthy had felt the wrath of the Jews when he had spoken out against the barbarous treatment of German prisoners five years earlier that made him wary of offending them again. His investigations into Communist subversion were turning up a vastly disproportionate number of Jewish Communists, and he was afraid that the Jews would believe he was hunting Jews rather than Communists.

By using the threat of investigation as a weapon to coerce the Army into giving special treatment to his friend Schine, Cohn had tainted the legitimacy of McCarthy’s patriotic work. Cohn was creating exactly the impression of reckless disregard for fairness and propriety that McCarthy had wished to avoid.

McCarthy had apparently hoped that the alleged anti-Communist Jews with whom he dealt were what they claimed to be. With their involvement, however, all his efforts met with grief. If the Senator had taken account of Jewish traits — especially their bent for deception, which goes far beyond anything encountered in the Gentile world — then perhaps he would have braved the charges of “anti-Semitism” rather than tolerate Jews on his staff.

The anti-Communist credentials of Jewish columnist George Sokolsky, for example, who had recommended Roy Cohn, were invented rather late in life. In 1917, at the age of 24, Sokolsky had gone to Russia with a large number of other Jews, filled with ardor for the prospect of world Communism and hoping to lend a hand to the Bolsheviks in fastening the Communist yoke on the Russians. For a while he edited the English-language Communist newspaper Daily News in Petrograd; then he left for China to practice his journalistic skills on behalf of the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen, who was working to set up a Communist government in China and was receiving aid from the Soviets. In 1931, claiming disillusionment with the methods of Bolshevism, he returned to the United States, where he used different methods.

As a right-wing columnist for the Hearst newspapers, Sokolsky was well-placed to accomplish much for the Jewish obsession with the New World Order by misdirecting the anti-Communist movement into blind alleys, false hopes, and confusion — and away from the truth. Considering these facts, are we justified in believing his claim that he had completely changed his ideals and in the 1950s was fervently against what he had been fervently for earlier in Russia and China? A clue may be provided by Sokolsky’s 1935 book, We Jews, in which he lamented the fact that Jews are not even more cohesive than they are. Certainly, no race-conscious Jew could have genuinely supported McCarthy’s efforts to root Communists out of positions of influence in American life, since he would have understood that exposing Communism meant exposing Jews.

Similarly, Roy Cohn, who called Sokolsky his “rabbi,” was another member of the far left who claimed a miraculous conversion: as late as 1949 he was openly calling anti-Communism a “witch-hunt” and said that Alger Hiss was a victim of a “right-wing conspiracy.” Given the legendary cohesiveness of the Jewish people and the Jewishness of Communism, one is justified in viewing these overnight conversions with suspicion.

There is more than Roy Cohn’s youthful attachment to leftist causes to make us suspicious of his motives: his father Albert Cohn had been the first judge appointed by Franklin Roosevelt after the latter became governor of New York. Thus, the Cohns were firmly attached to the very clique that had fostered what McCarthy called “twenty years of treason.”

It looks very much as if McCarthy, who wished so much to avoid crossing the Jews, allowed himself to be swindled in the age-old game of Good Jew/Bad Jew.

Ike and McCarthy

The man whom Eisenhower had appointed Secretary of the Army, Robert Stevens, head of the J.P. Stevens textiles business, was staunchly anti-Communist, having witnessed the pernicious influence of Communists in exacerbating labor disputes. Stevens was even distrustful of New Deal supporters. He was thus appointed not as a member of the New World Order clique around Ike, but merely as a valuable (if misguided) Republican booster. Stevens had apparently taken Eisenhower’s anti-Communist campaign rhetoric at face value.

Upon assuming office in February 1953, Stevens requested a briefing on the Army’s Loyalty and Security Program: “The presentation should set forth what steps are to be taken to prevent disloyal and subversive persons from infiltrating the Army, and what steps have been taken to discover and remove such persons who may have found their way into the Army Establishment.” So concerned was Stevens about combatting subversion that he asked advice from J. Edgar Hoover, director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Finally, when Stevens heard that McCarthy was concerned about security risks in the Army, he rushed a telegram to him, offering his assistance in the investigation.

McCarthy’s staff announced on September 10, 1953, that there was very serious evidence of espionage at Fort Monmouth. The evidence was an extract of a report from J. Edgar Hoover to the head of Army Intelligence. The document mentioned 35 Fort Monmouth employees as security risks, most of them Jews of Russian origin who had been in contact with the atom-bomb spies, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Stevens instructed the commanding general at Fort Monmouth: “Cooperate! See to it that they interview anyone they wish to.”

During the investigation at Fort Monmouth, however, attention was diverted to nearby Camp Kilmer. This was the case of the Jewish Communist Irving Peress. Peress, an Army dentist who was proved to be not only a member but an organizer of Communist groups, had sworn a false oath upon receiving his officer’s commission. Worse, when the matter was exposed Peress was promoted and later given an honorable discharge, thus escaping the jeopardy of a court-martial. The Peress case was a tremendous embarrassment to the Army, because it showed that security in the Army was a mere formality which was easily circumvented.

McCarthy’s confidential informant on the Peress case was General Ralph Zwicker. A hearing in New York City was arranged, and General Zwicker was called to testify as to the identity of the Pentagon official who had ordered Peress’ honorable discharge. On the very morning of the hearing, however, Zwicker received an order from John Adams not to reveal the official’s name. McCarthy did all he could to persuade Zwicker to talk in spite of the order, but he failed.

Thereafter the press made a great fuss over McCarthy’s rough treatment of Zwicker and the “insult to the uniform.” It was alleged that McCarthy had without cause accused Zwicker of shielding subversives.

Secretary Stevens decided not to allow General Zwicker or other Army officers to testify further. Says William Ewald, a Department of Defense official at the time: “A cheer went up: from anti-McCarthyites within the Administration itself, from editorial writers far and wide, from liberals coast to coast.” Especially noteworthy was a telephone call to Stevens from Marshall Plan administrator Paul Hoffman in California — at whose residence Eisenhower was then vacationing. This congratulation was inferred to represent the attitude of that champion McCarthy-hater, President Ike.

Eisenhower’s friend Hoffman was married to Anna Rosenberg, who had been Truman’s Jewish Assistant Secretary of Defense in 1950 and had been diligent in promoting liberal programs in the Army and the other armed services. She, more than anyone else, had forced full racial integration on the services.

Unlike Ike, however, Secretary Stevens was not an implacable foe of McCarthy and anti-Communism. Although he thought Roy Cohn was awful, he said he saw McCarthy as a “reasonable” man. In a conference with the majority members of McCarthy’s subcommittee, an agreement was reached and Stevens signed a document that stated this accord. The anti-McCarthy interpretation of this event has been that Secretary Stevens did not understand what he was doing. More likely, Stevens did not understand what Eisenhower was doing. Nor did the American people understand!

Stevens said of the media’s explosively hostile reaction to his reconciliation with McCarthy, “I think I have been absolutely crucified. . . .” Furthermore, he showed naiveté by saying that he thought the press had “misunderstood” the agreement.

Eisenhower decided to have Secretary Stevens “admit an administrative error” and renege on the agreement. A repudiation of Stevens’ agreement with McCarthy was composed, and Stevens was made to read it publicly.

Meanwhile, President Eisenhower’s staff, without Stevens’ knowledge, had instructed Stevens’ subordinate John Adams to compile a written record of Cohn’s and Schine’s behavior. Adams, a holdover from the Truman administration, apparently was considered more politically reliable than the conservative Stevens.

On March 8, 1954, when Secretary Stevens was asked about the record of improper pressure by Cohn and Schine (which John Adams had leaked to the press a few days earlier) he said, “I personally think that anything in that line would prove to be very much exaggerated. . . . I am the Secretary, and I have had some talks with the committee and the chairman . . . and by and large as far as the treatment of me is concerned, I have no personal complaints . . . .”

On March 10, although Stevens had not even been aware of the Schine chronology two days earlier, he was pressured into approving a version heavily “revised” by Defense Department attorney Struve Hensel. It was called the “Stevens-Adams chronology,” although Stevens had only just learned of it. Under pressure, the Secretary of the Army was now lending his name to a document that he had said would be “very much exaggerated.”

The Army-McCarthy Hearings Commence

In late April 1954 the Army-McCarthy hearings began. The Army had accused McCarthy and Roy Cohn of using improper pressure, evidence of this being the so-called “Stevens-Adams chronology.” McCarthy counter-charged that the Army was trying to discredit his committee and stop its investigation of the Army.

During the hearings Stevens was the Army’s “star witness.” He “stonewalled” the subcommittee, giving vague, unresponsive, and often self-contradictory testimony. It became clear to McCarthy that Stevens was acting under orders from Eisenhower’s staff. The Army’s case, however, already had been blown sky-high, and McCarthy essentially vindicated, when Senator Everett Dirksen, a member of the McCarthy Subcommittee, testified that the Army’s counsel John Adams and Eisenhower’s administrative assistant Gerald Morgan had approached him on January 22, 1954, seeking to stifle part of McCarthy’s investigation of the Army. Dirksen testified that Adams had mentioned the Army’s file on Cohn and Schine, dropping a “hint” that these files might be very damaging if they were “issued and ventilated on the front pages” of newspapers.

At this point, John Adams, not wishing to be the lone scapegoat for Eisenhower, and, furthermore, living under the possibility of a prosecution for perjury, revealed that he had been told to compile the chronology on Cohn and Schine by members of Eisenhower’s staff in a secret meeting in the Attorney General’s office the day before approaching Dirksen.

The White House was now clearly implicated in a conspiracy to shield subversion in the government. On May 17 Eisenhower, in an obvious attempt to prevent his own role from being investigated further, issued what became known as the “iron curtain” order. Eisenhower claimed that it was a Constitutional principle that the President could forbid his subordinates from revealing any information to the Congress.

On May 27, after several more days of vague, unresponsive, and sometimes conflicting testimony from Stevens, McCarthy responded in exasperation to Eisenhower’s gag order: “The oath which every person in this government takes, to protect and defend the country against all enemies, foreign and domestic, that oath towers far above any presidential security directive.” He urged federal employees to come forward with any information they might have about corruption and subversion in government.

The next day Eisenhower had his press secretary convey to the media a statement that likened McCarthy to Hitler: a comparison that was not meant to flatter McCarthy. Edward R. Murrow and other media figures took their cue and began echoing that line.

McCarthy, however, was expressing essentially the same idea which Theodore Roosevelt had expressed half a century earlier, when the latter said:

“It is patriotic to support [the President] insofar as he efficiently serves the country. It is unpatriotic not to oppose him to the exact extent that by inefficiency or otherwise he fails in his duty to stand by the country. . . . In any event, it is unpatriotic not to tell the truth–whether about the President or anyone else.”

And of course, the truth was exactly what Ike feared. Was this not the Eisenhower who had carried out Operation Keelhaul after the Second World War, in which anti-Communist Russians, Hungarians, and others were forcibly repatriated to a certain death under Communism? Was this not the Eisenhower who deliberately starved to death over a million German prisoners of war? And was this not the same Eisenhower who later sent paratroopers into Little Rock to enforce racial integration with bayonets?

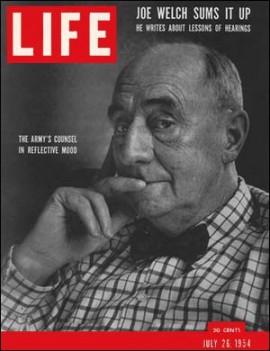

Regardless of the legal result, biased media coverage made the Army-McCarthy hearings a propaganda victory for the pro-Communists. Army counsel Joseph Welch, through hyperbole and histrionics, managed to convince a large portion of the public that a few peripheral issues he raised during the hearings were serious embarrassments to McCarthy.

Welch, the Television Cameras, and the End

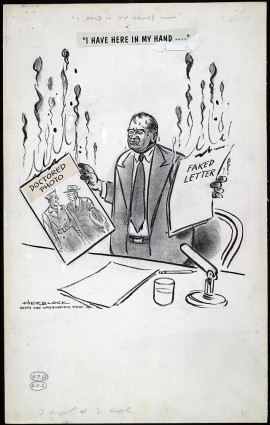

For example, Welch insisted for the television cameras that part of an FBI report listing subversives at Fort Monmouth was “a carbon copy of precisely nothing” and “a perfect phoney,” even though FBI Director Hoover said that he had written it. Similarly, Welch dramatically accused McCarthy of introducing a “doctored” photograph into evidence: it was a quite genuine photograph, which merely had been cropped and enlarged for the sake of clarity. The media played up Welch’s accusations and ignored McCarthy’s explanations.

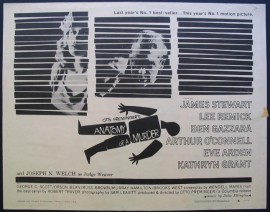

Welch was much more an actor than a lawyer: later, in 1959, he starred in a major Hollywood production, Anatomy of a Murder, alongside Jimmy Stewart and Lee Remick. In any event, during the Army-McCarthy hearings the Senate hearing room was his stage, and he played his role to the hilt. When McCarthy pointed out that a member of Welch’s own law firm, Fred Fischer, had been a member of the National Lawyers’ Guild, an organization cited as a Communist front by the Attorney General, Welch waxed maudlin and sobbed the famous line, “Have you no sense of decency at long last?” Later, outside the hearing room, Welch wept again for the benefit of the news photographers. (Welch’s goading of McCarthy and tearful denouement may have been planned in advance; see Appendix below. — Ed.)

As reported by the media, Welch was a man of great humanity who was shocked that McCarthy would be so ignoble as to attempt to ruin Fischer’s career with his accusation, while McCarthy was a heel for even raising the matter. The fact that McCarthy’s charge was perfectly accurate seemed to make no difference at all to the media.

And so it was with other episodes in the hearings. One contemporary observer, Harold Varney, noted in the American Mercury:

“Unfortunately, the anti-McCarthy press was not honest enough to admit publicly that the Senator had been vindicated. The smearers continued to parrot the smears, just as if the disproof were not before the country.”

The masters of the controlled media were determined to “get” McCarthy, and they did. They had not directed as much hatred on any public figure since Adolf Hitler.

By September many of his supporters in the Congress, ever sensitive to the direction of the political wind, had thrown in the towel. McCarthy’s Senate colleagues stripped him of his committee chair in November. On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted 67-22 to condemn him for “conduct contrary to Senatorial traditions.” The condemnation permanently ended his effectiveness as a legislator.

* * *

Additions and annotations by Kevin Alfred Strom; originally published in 1994; American Dissident Voices broadcast series title “Joe McCarthy: Tragic hero.”

APPENDIX

The Set Up: Welch and McCarthy

MANY BELIEVE that Welch set up McCarthy through his breaking of a pre-hearing agreement and threatening to expose Cohn and Schine as homosexuals. According to writer Brian Burns:

The quote, “Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?” was asked of the notorious Senator Joe McCarthy by Attorney Joseph Welch at the climactic moment of the Army-McCarthy Hearings, a 55-day spectacle that riveted the attention of the nation in the spring of 1954.

A grandfatherly, bespectacled man with a fondness for neckties, Walpole’s Welch was the lead counsel for the Army during the hearings, which aired live on the ABC and DuMont networks.

Welch’s memorable excoriation of McCarthy came as the bullet point of a tearful and impassioned speech in which he blasted McCarthy for his “cruelty and recklessness.” It was a moment that would forever alter the lives of both men….

Welch, an attorney at the Boston law firm of Hale and Dorr, was hired to represent the Army….

The penultimate confrontation with the Wisconsin senator came on June 9, while Welch was needling Cohn in cross examination about the contention that there were 130 known Communists working in Army labs throughout the country.

After stewing for a while in the background, McCarthy finally interjects after Welch playfully asks Cohn why he doesn’t just have the FBI get all of the Communists out of the Army by sundown.

McCarthy tells Welch that one of his co-workers at Hale and Dorr, “a young man named Fischer,” had belonged for three or four years to the National Lawyers Guild, an organization that was named “years and years” ago as the legal bulwark of the Communist party.

Since Welch was so interested in ferreting out Communists, he should be made aware of the fact that Fischer was a member of his own firm, McCarthy said. Welch’s response was brutally effective.

Welch: ‘Until this moment, Senator, I think I never really gauged your cruelty or your recklessness. Fred Fischer is a young man who went to the Harvard Law School and came into my firm and is starting what looks to be a brilliant career with us. When I decided to work for this committee, I asked Jim St. Clair, who sits on my right, to be my first assistant. I said to Jim, “Pick somebody in the firm to work under you that you would like.” He chose Fred Fischer, and they came down on an afternoon plane. That night, when we had taken a little stab at trying to see what the case was about, Fred Fisher and Jim St. Clair and I went to dinner together. I then said to these two young men, “Boys, I don’t know anything about you, except I’ve always liked you, but if there’s anything funny in the life of either one of you that would hurt anybody in this case, you speak up quick.”

‘And Fred Fisher said, “Mr. Welch, when I was in the law school, and for a period of months after, I belonged to the Lawyers Guild,” as you have suggested, Senator.

‘He went on to say, “I am Secretary of the Young Republican’s League in Newton with the son of [the] Massachusetts governor, and I have the respect and admiration of my community, and I’m sure I have the respect and admiration of the twenty-five lawyers or so in Hale & Dorr.”

‘And I said, “Fred I just don’t think I’m going to ask you to work on the case. If I do, one of these days that will come out, and go over national television and it will just hurt like the dickens.” And so, Senator, I asked him to go back to Boston.

Little did I dream you could be so reckless and so cruel as to do an injury to that lad…It is, I regret to say, equally true that I fear he shall always bear a scar needlessly inflicted by you. If it were in my power to forgive you for your reckless cruelty, I would do so.

‘I like to think I’m a gentle man, but your forgiveness will have to come from someone other than me.’

McCarthy: ‘Mr. Chairman, may I say that Mr. Welch talks about this being cruel and reckless. He was just baiting; he has been baiting Mr. Cohn here for hours, requesting that Mr. Cohn before sundown get out of any department of the government anyone who is serving the Communist cause. Now, I just give this man’s record and I want to say, Mr. Welch, that it had been labeled long before he became a member, as early as 1944.’

Welch: ‘Senator, may we not drop this? We know he belonged to the Lawyers Guild. And Mr. Cohn nods his head at me. I did you, I think, no personal injury, Mr. Cohn?’

Cohn: ‘No, sir.’

Welch: ‘I meant to do you no personal injury, and if I did, I beg your pardon. Let us not assassinate this lad further, Senator. You’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir, at long last? Have you left no sense of decency?’

Welch’s stirring condemnation was the beginning of the end for McCarthy, who would be censured by the Senate later that year.

Following his censure McCarthy returned home to Wisconsin, where he died of complications from alcoholism in 1957. He was only 48.

Welch, on the other hand, found himself a national celebrity. His exposure of McCarthy’s bluster earned him high praise from the media and various civic organizations and his stirring speech secured him a permanent place in the annals of history.

…While there is little question of the effectiveness of Welch’s condemnation, recent evidence has suggested that it may not have been as spontaneous as it seemed to those who watched it unfold live on the air.

A number of historians now believe that McCarthy may have blundered his way into a carefully planned trap.

One of the strongest advocates of this theory is Nicholas von Hoffman, who describes the encounter from Cohn’s perspective in Citizen Cohn (The Life and Times of Roy Cohn. Doubleday). Von Hoffman writes that despite the animosity between the two parties, Welch and McCarthy agreed before the trial that several areas would be off limits.

Welch agreed that he would not mention Cohn’s avoidance of the draft during World War II. In return, McCarthy’s camp agreed that they would not bring up Fischer’s membership in the Lawyer’s Guild.

Von Hoffman and several other sources suggest that the agreement also extended to Cohn’s sexual orientation. Though he denied it to his dying day, Cohn was widely known as a homosexual, especially to the Washington insiders that packed the hearing room each day.

According to several sources, it is possible that Welch had intentionally provoked McCarthy earlier in his cross examination by showing Cohn a picture that had been doctored by the McCarthy camp prior to being submitted as evidence.

After Cohn offers no explanation for how the altered picture came to be, Welch playfully asks him if it might have been created by a pixie. McCarthy angrily jumps in.

McCarthy: ‘Will the counsel for my benefit define — I think he might be an expert on that — what a pixie is?’

Welch: ‘Yes, I should say, Senator, that a pixie is a close relative of a fairy. Shall I proceed, sir? Have I enlightened you?’

At this point, according to sources, the room erupted in laughter. It was a dig at Cohn’s expense, but it wasn’t a direct violation of the agreement, a subtle point that may have been lost on McCarthy.

Von Hoffman quotes from Michael Straight, who wrote about the moment in the New Republic.

“As law the comment was improper; as humor it was unjust; as drama it was beyond anything that the theatre could conceive or reproduce.”

Was this dig, and Welch’s subsequent needling about getting all the Communists out by sundown, designed to lure McCarthy into making a foolish attack on Fischer?

There seems to be some legitimacy to this argument, especially when one considers the way that McCarthy later reacts.

McCarthy: ‘Mr. Chairman, may I say that Mr. Welch talks about this being cruel and reckless. He was just baiting; he has been baiting Mr. Cohn here for hours…’

Cohn, a talented if unscrupulous lawyer in his own right, is smart enough not to respond to Welch’s thrust and later tries to dissuade McCarthy from pursuing his inquiry into Fischer, though it is to no avail.

Welch: ‘Senator, may we not drop this? We know he belonged to the Lawyers Guild. And Mr. Cohn nods his head at me. I did you, I think, no personal injury, Mr. Cohn?’

Cohn: ‘No, sir.’

Yet McCarthy insists on pursuing the issue, sealing his own fate at the hands of Welch’s eloquence.

Without asking Welch himself, it’s difficult to know how much of his speech was real and how much was part of a carefully designed plan. This anecdote recounted by von Hoffman seems to suggest that it was a bit of both.

“Welch had tears in his eyes as he delivered the last line; they were rolling down his cheeks as he left the center area; he passed a young reporter named John Newhouse who had been late and had to accept standing room by the door. As Welch went by, tears still coursing, he looked at Newhouse and winked.”