There are profound lessons for us today in the saga of this misled hero.

by Scott Speidel, Florida State University

* * *

“Average Americans can do very little insofar as digging Communist espionage agents out of our government is concerned. They must depend upon those of us whom they send down here to man the watch-towers of the nation. The thing that I think we must remember is that this is a war, which a brutalitarian force has won to a greater extent than any brutalitarian force has won a war in the history of the world before.

“You can talk about Communism as though it’s something ten thousand miles away. Let me say it’s right here with us now. Unless we make sure that there is no infiltration of our government, then just as certain as you sit there, in the period of our lives you will see a Red world.

“Anyone who has followed the Communist conspiracy, even remotely, and can add two and two, will tell you that there is no remote possibility of this war which we are in today — and it’s a war, a war which we’ve been losing — no remote possibility of this ending except by victory or by death for this civilization.”

* * *

THOSE WORDS were spoken 40 years ago by U.S. Senator Joseph Raymond McCarthy, Republican of Wisconsin, a man who since has been demonized unjustly. Since McCarthy’s time the subversion of our nation has proceeded steadily, and his warning to us resonates more and more clearly as truth, now that death for this civilization is in view.

Joseph McCarthy’s fame as an anti-Communist began with a speech he delivered on February 9, 1950, to the Republican Women’s Club in Wheeling, West Virginia, in which he said that there were at least 57 known Communists in the U.S. State Department, and that the State Department knew they were there.

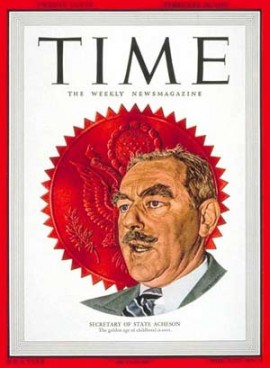

McCarthy’s charge was credible, because President Harry Truman’s Secretary of State at the time, Dean Acheson, was well known as a man sympathetic to Communism and Communists. As far back as the 1930s Acheson had worked as a lawyer on behalf of Stalin’s regime, prior to the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union by the United States, and recently he had ignored reports about the Communist Party connections of his protege at the State Department, Alger Hiss. Acheson also had been the chief U.S. advisor at the Yalta Conference, in February 1945, which consigned eastern Europe to Communist rule, and he presided over the drafting of the United Nations Charter. In the State Department Acheson fostered the careers of Communists and stifled the careers of anti-Communists.

Furthermore, as Ohio’s Republican Senator Robert Taft said at the time, “Pro-Communist policies of the State Department fully justify Joe McCarthy in his demand for an investigation.”

Grand Scale of Subversion

Communist infiltration of the U.S. government had occurred on a grand scale during the reign of Franklin Roosevelt. Congressman Martin Dies, Democrat of Texas and chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities from its inception in 1938 until 1945, had warned Roosevelt in 1940 that there were thousands of Communists and pro-Communists on the government payroll, but FDR refused to take action, saying:

“I do not believe in Communism any more than you do, but there is nothing wrong with the Communists in this country. Several of the best friends I have are Communists. . . .

“I do not regard the Communists as any present or future threat to our country; in fact, I look upon Russia as our strongest ally in the years to come. As I told you when you began your investigation, you should confine yourself to Nazis and Fascists. While I do not believe in Communism, Russia is far better off and the world is safer under Communism than under the Czars.”

Under the circumstances, McCarthy’s charge that there were 57 known Communists in the State Department seems very modest.

A Maverick for the Truth

McCarthy had been a maverick from the beginning. In 1949 he had dared champion the cause of German prisoners of war held in connection with the alleged “Malmédy massacre.” In truth, what had happened near the Belgian town of Malmédy in December 1944 was unclear at the time, part of what U.S. General Thomas T. Handy, who in 1949 was the commander in chief of U.S. forces in Europe, called “a confused, mobile, and desperate combat action.” It is known now that a number of American soldiers who had surrendered there to the Germans were shortly thereafter killed in cross fire when their captors, who were marching them to a rear area, were engaged by other U.S. units. When their bodies were found by U.S. forces afterward with their hands tied behind their backs, however, it appeared that they might have been deliberately killed.

After the war, Germans who had taken part in the fighting at Malmédy were turned over to U.S. Army Colonel A.H. Rosenfeld and his Jewish underlings for “interrogation.” The prisoners were arbitrarily reduced to civilian status so that they would not be protected by the Geneva Convention, and brutal torture was used to extract confessions. When 18-year-old prisoner Arvid Freimuth hanged himself after repeated beatings rather than sign a “confession,” the prosecutors were permitted to use as “evidence” the unsigned statement which they themselves had contrived.

McCarthy dared to speak against this officially sanctioned lynching, when almost no one else had the courage to do so. By fearlessly championing the underdogs, the defeated and vilified Germans, and speaking out against the actual atrocities committed by self-righteous aliens in American uniform, the Senator demonstrated the rare moral courage that later propelled him into the forefront of the struggle against Communism.

The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Senator Raymond Baldwin, Republican of Connecticut, was assigned to investigate the charges of torture, but whitewashed them instead. On July 26, 1949, Senator McCarthy withdrew in disgust from the hearings and announced in a speech on the Senate floor that two members of the Committee, Senator Baldwin and Senator Estes Kefauver, Democrat of Tennessee, had law partners among the Army interrogators they were supposedly investigating. This was in several ways a preview of things to come.

The Jews showed instant hostility toward anyone who interfered with their campaign of vengeance against the conquered Germans, and so they began turning their big guns in the media against McCarthy: a December 1949 poll of news correspondents covering the United States Senate already had reporters branding McCarthy “the worst Senator” — a high honor indeed.

Patriotic Motivation

When McCarthy had arrived in Washington as a freshman Senator in 1946, he had been invited to lunch by Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. McCarthy writes:

“Before meeting Jim Forrestal I thought we were losing to international Communism because of incompetence and stupidity on the part of our planners. I mentioned that to Forrestal. I shall forever remember his answer. He said, ‘McCarthy, consistency has never been a mark of stupidity. If they were merely stupid they would occasionally make a mistake in our favor.’ This phrase struck me so forcefully that I have often used it since.”

Considering the destructive policies that thrived in Washington, McCarthy concluded that to fight Communism effectively it was not enough to denounce Communism in general; anyone — even a Communist — could claim to oppose Communism. The Senator decided that it was necessary to identify those responsible for treasonous policies and then accuse them on the basis of what they actually had done, not on the basis of the ideas to which they paid lip service.

A special investigating subcommittee chaired by Senator Millard Tydings, Democrat of Maryland, was set up purportedly to investigate McCarthy’s claim that Communists and pro-Communists were being harbored in the State Department. In reality, as Tydings himself admitted, the purpose was to silence McCarthy. Tydings boasted, “Let me have McCarthy for three days in public hearings, and he will never show his face in the Senate again.” Tydings’ effort to discredit the upstart patriot would be heavily aided by the major media.

One of the reporters present at the hearings was Elmer Davis, a prominent radio commentator who had been head of the Office of War Information (OWI). McCarthy noted:

“Many of the [principals in the] cases I was about to present had once been employees in the OWI under Davis and then had moved into the State Department. As I glanced at Davis I recalled that Stanislaw Mikolajczyk, one of the anti-Communist leaders of Poland, had warned the State Department, while Davis was head of the OWI, that OWI broadcasts were ‘following the Communist line consistently,’ and that the broadcasts ‘might well have emanated from Moscow itself.’ There could be no doubt how Davis would report the story. . . .

“At one of the other tables I saw [left-wing, muckraking columnist] Drew Pearson’s men. I could not help but remember that Pearson had employed a member of the Communist Party, Andrew Older, to write Pearson’s stories on the House Committee on Un-American Activities and that another one of Pearson’s limited staff was David Karr, who had previously worked for the Communist Party’s official publication, the Daily Worker. No doubt about how Pearson would cover the story. . . .

“As I waited for the chairman to open the hearing I, of course, knew the left-wing elements of the press would twist and distort the story to protect every Communist whom I exposed, but frankly I had no conception of how far the dishonest news coverage would go.”

In the case of Owen Lattimore, the testimony of McCarthy’s chief witness, ex-Communist Louis Budenz, was widely misrepresented. Lattimore was a scholar on Far Eastern affairs employed by the State Department as a consultant; he had advised the State Department that Chinese Communist leader Mao Tse-Tung was merely “a liberal agrarian reformer” at a time when Washington was still unsure how to react to Mao’s efforts to overthrow the Chinese government. In McCarthy’s words:

“[Budenz] . . . testified that . . . [Lattimore], who had been employed by the government, consulted for years by State Department officials on Far Eastern policy, and looked to by newspapermen and magazine editors for news on Far Eastern trends, had been a member of the Communist Party.”

Reporters, Some of them Honest

Many newspapers and wire services so twisted Budenz’s testimony about Lattimore, however, that it was not clear to most Americans that Lattimore had indeed been identified positively as a Communist.

One honest reporter, Dave McConnell of the New York Herald Tribune, wrote in the May 16, 1950, edition of his now defunct paper that “you have to use a sieve to strain out the bias in the McCarthy stories published in many papers.”

“Tail-gunner Joe,” as McCarthy was nicknamed by the press, was seen by many as a national hero. A Gallup poll taken May 21, 1950, showed that among the general public he had four supporters for every three detractors. In a later Gallup poll, taken in January 1954, 50 per cent. of the public viewed him favorably, and 29 per cent. viewed him unfavorably. McCarthy was the one man in Washington, D.C., who bucked the bipartisan pressure to be polite to America’s enemies and to “get along by going along.” He was the one man who took anti-Communism seriously and was willing to do something about it.

At the time conservative writer Harold Lord Varney wrote in the American Mercury:

“McCarthy is where he is today because he satisfies the deep national hunger for an affirmative man. In a Washington of vacillating, irresolute, pressure-group-cowed politicians, he stands out in sharp relief as a man sure of himself. His unshaken self-confidence is shown by the opponents he has tackled: they have been Marshall, Acheson, Tydings, Conant — men in the full tide of their authority. And he has never lost a major Washington fight. . . .

“He sometimes gets too far out in front of public opinion, but so far public opinion has always followed him. . . .

“Because McCarthy has been willing to act as the shock absorber of the main stream of pro-Communist abuse, the careers of all [other] anti-Communists have been made easier. . . .

“One far-reaching consequence of [McCarthy’s fight] has been its impact upon the American world of ideas. The climate of American public discussion has been amazingly cleared since McCarthy began to fight. . . . The long grip on the nation’s communications media exercised by the literary Reds and Pinkos has been broken. . . .”

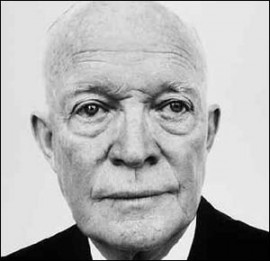

This is all very different, of course, from today’s popular conception, which was molded by the controlled media. Little is said of McCarthy’s popularity, which even Eisenhower dared not challenge directly. Instead, we are led to believe that McCarthy was a brutal tyrant who somehow managed to run roughshod over everyone’s civil liberties and give the entire country a very bad case of claustrophobia for several years, all of this as chairman of a Senate subcommittee.

McCarthy’s Methods

Make no mistake about it, McCarthy did cause considerable discomfort to some people: to the alien subversives and traitors whose ultimate goal was and still is the New World Order. It was these people who, in their effort to silence McCarthy, ironically characterized him as an enemy of free speech. The First Amendment, of course, had been drafted precisely to protect men like McCarthy, who dared to identify treason in high places.

There were undoubtedly, however, some sincere, patriotic Americans who agreed with McCarthy’s aim of removing Communists from government, but who found his method, with all of its sensationalism and public-relations gimmickry, distasteful. McCarthy’s method was, as he himself explained, a last resort:

“I have followed the method of publicly exposing the truth about men who, because of incompetence or treason, were betraying this nation. Another method would be to take the evidence to the President and ask him to discharge those who were serving the Communist cause. A third method would be to give the facts to the proper Senate committee which had the power to hire investigators and subpoena witnesses and records. The second and third methods . . . were tried without success. . . . The only method left to me was to present the truth to the American people. This I did.”

People who criticized McCarthy’s public accusations merely as being in poor taste clearly did not appreciate the gravity of the situation and the necessity for taking action. Also it should be noted that McCarthy had not wanted to read his original list of 57 subversives publicly, but the Tydings Committee required it of him. According to the Congressional Record of Feb 20, 1950, p. 2049, McCarthy protested on the Senate floor:

“I think . . . it would be improper to make the names public until the appropriate Senate Committee can meet in executive session and get them. . . . It might leave a wrong impression.”

Unfortunately, “the wrong impression” was exactly what the Tydings Committee wished to promote. In other words, contrary to the reputation for “recklessness” that was applied to him, McCarthy exercised his First Amendment right with great care.

Republicans Without Honor

Like some resurrected Paul Revere or latter-day Cicero, it was he who sounded the alarm, who let the American people know that their government had been subverted by alien interests; and it was the shadow government of “globalists” who wished to silence him, so that their power and their pernicious influence would remain hidden from the American people.

International Communism and international finance — the twin thrusts of Jewish power — were both ill-served by the attention McCarthy drew to the issues of loyalty and subversion.

In the 1952 elections the Republicans captured both houses of Congress and the Presidency, largely due to McCarthy’s influence. McCarthy became chairman of the Senate’s Government Operations Committee and its Subcommittee on Investigations. The new President, however, was a pet of the New World Order clique, and he would succeed where Truman had failed in discrediting McCarthy.

In the discrediting of McCarthy, there is no doubt that there was a conspiracy at work. We know this because men who were privy to the conspiracy later wrote books about it. The activities of the conspirators were, of course, necessarily subtle; Eisenhower himself studiously avoided even mentioning McCarthy’s name in public, and the media coverage was almost unbelievably biased. Thus, for the general public, the arrangements which brought down McCarthy were a mystery, though in essence they were very simple: McCarthy was maneuvered into an awkward position, the major media portrayed him as unfavorably as possible, and his colleagues deserted him.